Jonathan Dunham is the eighth great-grandfather of the 44th President of the United States, Barack Obama. He is also the first of Obama’s Dunham ancestors to be born in America. Yet he wasn’t born a Dunham.

Instead, he was born Jonathan Singletary on Jan. 17, 1639 (or maybe 1640) in the northern Massachusetts town of Newbury. He was the oldest of seven children of Richard Singletary, who came to America from Surfleet, a town near England’s east coast.

As for his mother, there are two possibilities. One is Lydia Downham, who apparently migrated to America along with Richard Singletary. Public records of the time refer to the Goodwife Singletary, who died in 1638 or 1639, although it isn’t clear whether she was Downham or whether there had ever been a marriage. The other is Susannah Cooke, who married him shortly after the Goodwife’s death.

Trouble in Massachusetts

Jonathan grew up in Newbury and the nearby towns of Salisbury and Haverhill, Massachusetts. He married Mary Bloomfield by 1662. when she is identified as Jonathan’s wife in a legal document. The paperwork concerned the transfer of a plot of land to her from her in-laws.

Why would Jonathan’s family make the transfer to Mary, rather than to him? Maybe it was because Jonathan led what one of his descendants, Audrey Shields Hancock, would later call “a stormy life.” She cited government records that accused him of being a Ranter, or part of a radical English religious group from the mid-1600s.

Jonathan was jailed in 1662 for refusing to pay debts owed to another man, John Godfrey. Events during his jail time led him to lodge witchcraft charges against Godfrey, who in turn sued for defamation and slander. Jonathan was found guilty and ordered in 1664 to pay a fine or make a public apology. The punishment he chose has been lost to history.

All this suggests Jonathan might have been ready for a change of scenery by 1665, when his father-in-law was invited by New Jersey’s first governor, Philip Carteret, to settle in the state.

Becoming Dunham

Jonathan and Mary migrated to Woodbridge, New Jersey, along with her parents in the second half of the 1660s, Although some accounts say they arrived as early as 1665, records show the couple had two children while in Killingworth, Connecticut, about halfway between Haverhill and Woodbridge.

Whenever they arrived, Woodbridge was just getting started. Puritans from Dunham’s region of Massachusetts acquired the area, including today’s towns of Carteret, Metuchen and Rahway, from Gov. Carteret in December 1666. England’s King Charles II then granted a charter to Woodbridge Township in June 1669.

After arriving in New Jersey, Jonathan adopted the Dunham surname, making him Jonathan Dunham alias Singletary. He and his children are known to have signed legal documents with “Dunham alias Singletary.”

The exact reason for the change is unclear. Some who believe the Goodwife Singletary was his mother also speculate her name might have been Humility Dunham, or at least that her last name was Dunham. Others suggest Jonathan was the grandson of a Dunham, possibly Francis Dunham, and he took back the family name.

Whatever the reason, Jonathan was the only one of Richard Singletary’s children to change his last name. The Dunham name was passed down to his children and to later generations, although some of them used the variations Donham and Dunnam.

`Man of Great Energy’

In 1670, Woodbridge made land grants to the township’s earliest settlers. Jonathan was allotted 213 acres in return for building a grist mill. The grant consisted of a nine-acre house lot east of Kirk Green, an area set aside for a religious meeting house; 48 acres west of parsonage lands, designated for a minister’s use; 120 acres of upland, or high ground, and 36 acres of meadows not yet laid out.

Woodbridge also provided Jonathan with 30 pounds in currency and all the sod he needed to build dams for the mill. He was allowed to keep 1/16 of the mill’s output as a toll. The agreement was ratified at a town meeting in June 1670, and the work was completed by the end of September. He received rights to the land in the form of a patent on Aug. 10, 1672.

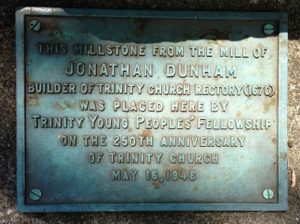

A stone from the mill, New Jersey’s first, and a historical marker are in front of the Jonathan Dunham House. The stone was used as a step into the house for many years before being moved to its current location.

Jonathan’s life in Woodbridge contrasted with his earlier turmoil in Massachusetts. Between 1671 and 1675, he served as a jury foreman, an overseer of highways, a tax assessor, the township court clerk and a member of a committee that defended Woodbridge’s interests in a border dispute. He was named as an attorney to defend the border in 1686, spent another term as assessor in 1694 and represented the township in the East New Jersey legislature in 1701.

“This Dunham was a man of great energy,” the Rev. Joseph W. Dally wrote in his history of Woodbridge and the surrounding area. “When he determined upon an enterprise he pushed it forward to success with indomitable perseverance.”

Several of Jonathan’s relatives settled near him, and the area just north of Kirk Green became known as Dunhamtown. Jonathan received another piece of property, located next to the northern part of his house lot, on May 19, 1696. This area may have included the land on which the Dunham House was built.

Overcoming Difficulties

Being in Woodbridge didn’t bring an end to Jonathan’s legal issues. In 1677, he and an accomplice, Robert Lapriere, were arrested for removing goods from the home of Gov. Carteret. The Council of War for Achter Colony, located in northern New Jersey, condemned him for the act and called for him to be punished as a “mad man.”

Six years later, Jonathan was convicted in a Massachusetts court on charges related to an incident at the home of another man, John Irish. He and a woman named Mary Ross, who were traveling together, burned Irish’s house and killed his dogs. A court in the New Plymouth colony ordered Jonathan to be publicly whipped and expelled.

The order noted that Jonathan had long been away from his wife and family and authorities had told him to go home. Though he eventually did just that, Ross came to Woodbridge in 1689 and was given land and a house. She returned the property to him in 1693.

Even with all the disruptions, Jonathan and his wife found time to have 10 children. The first one, Esther, was born in Massachusetts along with Mary, who died at about 2 years old, and a second Mary, possibly Sarah Mary. Ruth and Eunice were born in Connecticut. Jonathan; David; Nathaniel, who died at 1; another Nathaniel, and Benjamin were all born in Woodbridge. For details about the children, click here.

The date of the elder Jonathan’s death has long been a mystery. One possibility is that he died before April 24, 1724, when the younger Jonathan stated in a legal document that his father had recently passed away. Another is Sept. 6, 1724, the date cited most often by genealogists, Yet the elder Jonathan might well have been long gone by then, as wills indicate he died between April 18. 1702, and April 2, 1705. The wills were found by researchers in connection with a 2019 archaeological dig, and their report gave an estimated year of death of 1704.

Jonathan is buried next to his house or nearby in Trinity’s churchyard, according to several historians. Yet the church doesn’t have any record of the location, and there’s no headstone to mark the grave site. This represents the last mystery of his life.